Weronika Książek: How do you define social change? How can you tell when it is happening?

Professor Katarzyna Januszkiewicz: Considering my research interests, social change, for me, is mainly a context underlying my activities. Sometimes this context drives subsequent changes, for example the need to adjust organizational solutions to new situations. At other times, however, the vector of this relationship is reversed and our institutional, organizational, group, and finally individual initiatives initiate or facilitate change.

It is important here to capture the two main strands of analysis – the structural and the functional one. In a case of the first one, I will use a metaphor: you take a picture and look for the before/after or was/is differences. This allows us to describe the change even though we don’t quite understand it. The second approach concentrates on the process. We record a film and observe the dynamics between elements, watch the relationships, and we look for correlations, and here the question “what has changed?” is less important than the question “how did this happen?”. These approaches offer two out of three classical pillars of knowledge of idiographic sciences: description and explanation. However, the essence of social change is not its detection or pointing it out – “behold the change!” – but finding one’s place within that change and forecasting the consequences of the change. This gives us the third element of the triad – prediction. Only this complete understanding of social change shows us the whole picture. Therefore, it is so difficult to answer the questions about what social change is and how one can recognize it. This description is reactive in nature. You take on the role of a behavioral actor. However, you can reverse the chronology of these events and begin with what is to happen, what kind of change you expect, and then recreate subsequent steps. And this is about designing social change.

Professor Mariusz Wszołek: Social change, from the design perspective, can be observed through the condensation of perceptions – individual manifestations which become repetitive or non-repetitive. I define it as a state of the system under observation because something that for the observer is new or unusual can right away be described as social change. Condensation of perceptions means collating repetitions or non-repetitions – the collection allows us to ask questions about the nature of change: is the change a result of step events (e.g., the experience related to the coronavirus pandemic) or is it a long-term process, e.g., laicization of the society, rising nationalisms or decline of formal education. In design science, change is part of the transformation design paradigm – an assumption where you build transition scenarios based on the relation between the status quo and the proposed state, in other words knowing A and B, you ponder how to transition from A to B. For example, we know that decreasing emissions of green house gases is an effective way of avoiding climate catastrophe – we know A (the situation is bad), we know B (how to avoid the catastrophe). However, a problem (or a challenge) remains: how (in a case of the economy based on growth) can we achieve it? After all, a change in one area will affect other areas — it transpires that turning off the tap with crude oil is insufficient.

A good example of a systemic approach to shifting social attitudes is the initiative of Janette Sadik-Khan and her team, who worked on making the streets of New York cyclist- and pedestrian-friendly. Through simple and inexpensive projects she convinced thousands of New Yorkers to start using bicycles, and change their lifestyle according to the ideas proposed by another exceptional New Yorker – Jane Jacobs. Nowadays New York couldn’t be further from the gloomy brutalist vision of Robert Moses. Even though it is a concrete jungle, it is conducive to good city living. I strongly recommend two books: The Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs and Street Fight by Janette Sadik-Khan, exactly in this order, because it clearly shows what it means to see the difference between the situation A and situation B (Jacobs), and undertake the effort to transition from A to B (Sadik-Khan).

What role do universities and researchers play in initiating social changes?

Professor Katarzyna Januszkiewicz: It cannot be understated that this role is paramount. Universities – whole communities of academic teachers and students – are forums for emerging ideas, which are developed in communities, not in silos and lone brains of individuals. Of course, throughout history, there were exceptional people who invented things that have changed the world and our understanding of it. These days, stories like this are also possible, but besides exceptionality, we also need the everyday, and a positivist approach. Here, we also observe a certain shift, a significant shift, in perception and definition of science. The traditional approach assumes a neutral role of the researcher who observes objects from the sidelines, like in a Petri dish that has not been contaminated by any other influences. However, these days, increasingly often the expectations towards research and the attitudes of researchers themselves presuppose transgression. We no longer watch the process of gradual desertion of office buildings, and await the end of this form of work to formulate conclusions but we intervene during that process, and observe the effects of the interventions. Researchers and universities not only describe the world, but also actively change it.

Professor Mariusz Wszołek: The fundamental role of universities is to shape attitudes of students and of the whole university community – I mean mainly research and creative attitudes. A research mindset is characterized by curiosity and readiness to pose, often uneasy, questions and to search for answers to these questions. The creative attitude is responsible for action. It refers to a particular mind agility and the ability to see the world in terms of possibilities. Moreover, the role of universities is not merely to initiate social changes, but to observe these changes, secure scenarios of transition, and explain the resulting consequences affecting the society.

I believe that the clue is not in initiating changes, but in leading and explaining how to align oneself with ongoing changes, how to cope with them, and finally, how to assimilate these changes or to oppose them. An interesting example is the current discussion about the so called Artificial Intelligence (AI). It seems to me that we are in a similar place that we were several decades ago, when a hammer, which contained all information, appeared — I mean the Internet. Large parts of the population could use that hammer in any way they wished, simultaneously adding pieces of their own history (online activity). It was a great hammer, you must admit. But since nobody told us how to use this hammer in a considered way, we have permanently nailed fake news, disinformation, digital exclusion, etc., to the wall of civilization. A similar challenge awaits us with respect to Artificial Intelligence. The current delight with AI’s computing abilities and its applications on the job market that we have been observing, basically exclude any thoughtful discussion on how to use the new hammer in a wiser way other than hitting people over the head with it. In fact, this is what change is about — about managing uncertainty, and this is a job for universities because no other institution wants to take it.

Our university employs researchers representing different research disciplines. Are there any particular areas of social change that would be of interest to sociologists, psychologists, cultural researchers, and other ones that would interest designers, management specialists and lawyers? Perhaps, you can design change only while working in interdisciplinary teams?

Professor Katarzyna Januszkiewicz: I think that researchers representing different disciplines have their favorite parts of the garden. The questions is, can they cultivate it in isolation? During the pandemic one of the main challenges in management was work organization. Transitioning to three different modes of working – telecommuting, onsite, and hybrid – posed a technological challenge, which we met relatively well. However, questions arose about the future, and it turned out that the answer required knowledge that exceeded the framework of one discipline. A research team working on the k-EZOP project analyzed the impact the new modes of work had on organizations, groups, and individuals. Drawing upon the cumulative knowledge from psychology, sociology and management science has cemented our conviction, which we have been carrying internally for a long time but rarely realized in practice, that we live in an n-dimensional world. Of course, we can still carry out research and design changes, including social changes, from the perspective of our separate disciplines, but it is not only ineffective, but also irresponsible. It is our duty as researchers to believe in science, and science indicates that by touching a system in one place, we trigger changes in its many other parts. Hence, it is difficult for me to imagine designing social change without analyzing its impact. I mean a serious analysis that extends beyond one or two disciplines.

Professor Wszołek, what socio-cultural aspects are the subject of social change designed in your research area?

Professor Mariusz Wszołek: Design means problem solving by diagnosing and providing adequate solutions for end users in a particular social role. I know that I have been repeating this on every forum, but clearly not loud enough. In the area of design, it is impossible to deny that design is a fundamental indicator of social change, but not in a sense of providing new useless mobile applications or another pair of Virtual Reality goggles (I am talking about you, Apple!), but in the sense of engagement of strategic interest groups. The change does not result from design (understood here as an outcome of a process), but from the engagement of end users. I very much like the concept of an active citizenship proposed by Daniela Sangiorgi. In a nutshell: design means shifting the responsibility for initiating an activity and its maintenance to the user (here in the role of an ambassador), i.e., an active citizen. However, it does not mean relieving designers from this responsibility. Designers are responsible for animating and moderating social change at the level of the design process. After all someone must begin somewhere.

Must all social changes be innovative?

Professor Mariusz Wszołek: I don’t like this word in general. Innovation merely means a change of manifestation within a framework of a particular category (e.g., the latest iPhone that is better than the previous model — once more, talking about you, Apple!). I am rather interested in the category of progress, in other words, in the development of new categories that do not compete with each other. Please note that innovation plays on the new-old concept, where something that is “new” means “current”, while something else (which was also “new” prior to the time when the newer one appeared) becomes “obsolete” because it cannot coexist with the current one. And the problem is that the “current new” will very shortly become obsolete. And it ends as usual: we drown the world in useless objects, convincing people that they need to buy new things and spend money they don’t have. We should rather become interested in progress, which means not changes within a category (a newer iPhone that pushes out an older iPhone), but mainly in developing our own categories, which not necessarily question the existence of other categories already in use.

Professor Katarzyna Januszkiewicz: Theoretically, we can, of course, develop a broad and extensive narration about definition and interpretation frameworks of these concepts. Analyze whether definitions are disjoint or if they contaminate... but in practical terms it does not matter. Social change can be described using many different qualifiers, which help to classify it in a certain category, but they do not change its meaning. Can social change be innovative? Yes. Must it be innovative? No, it doesn’t have to be. Sometimes “new is coming back”, and this is also a change.

Is the development of new technologies our ally in making social changes or quite the contrary?

Professor Katarzyna Januszkiewicz: Recently, new technologies have been talked about so much that it is hard to resist a feeling that this topic has taken on a life of its own. I think that our basic assumption should be to recognize that new technologies are a tool, a kind of an instrument that is at our disposal. Whether we use them and in what way is our decision, so I would rephrase the question, and I would not search for an answer to the question whether the new technologies are an ally or an enemy, but rather when they simulate and when they inhibit the process of social change. And here I would like to go back to our assumption. Intentional use of tools provides us with an opportunity to obtain support for processes. Just as we cannot ignore the existence of new technologies (after all it is a very broad category), we cannot be passive about them either. The development of AI has been changing our world, including the world of organizations, but it does not mean that we must accept technological determinism. Of course, there is an option where diffusion of new technologies exerts pressure on social change, but sometimes social pressure leads to new solutions or new uses of the existing ones. And I think that the dynamics of these processes is the most important in this matter.

Professor Mariusz Wszołek: If the question refers to the ubiquitous awe of computing power of the new version of Chat GPT (Generative Pre-training Transformer), this only proves that we have reduced technology to the level of mental masturbation on the way to exclusion and stratification. If technological development is so fast and is supposed to be our ally in the process of social change then why we still have not solve the problem of famine around the world, the lack of access to clean drinking water, economic stratification or – and here is the irony! – digital exclusion?

What traits should designers of effective solutions that meet the needs of users, posses?

Professor Mariusz Wszołek: Such individuals should be curious about the world and other people, should be ready to ask difficult questions, and be able to independently search for answers. A social change designer should be a person who sees the world as full of possibilities, not limitations, someone with mental agility. Finally, it should be someone for whom the limits of design are set by problems that need solving.

Professor Katarzyna Januszkiewicz: In teams that specialize in organizational behavior we talk about transformative behaviors, i.e., behaviors that result in change. These behaviors are grounded in some specific characteristics, which in my opinion are indispensable for designing appropriate organizational solutions. Firstly – commonly shared values, i.e., this condition requires that employees regard the same values as those manifested by the organization as important. Secondly – co-participation, i.e., engagement in organizational matters arising from the alignment of employees' own values with the values of the organization. This means shifting form transactional thinking to relational thinking. Thirdly – co-creation, i.e., abandoning the tradition of behavioristic actor and assuming a proactive attitude, detecting cognitive signals, and shaping them into change. Please note that these characteristics have nothing to do with professional or trade skills. They are universal and in a sense separate people into change-makers and change-receivers.

What does the process of designing social change looks like from a design perspective? Is it different from product or service design?

Professor Mariusz Wszołek: There is no design other than design. In case of our initiatives concerning legal design, we follow the logic of the design process. We follow this logic regardless of the task – whether we design a chair, packaging, or unspecified form of communication. This logic includes several basic steps. In design the starting point is the problem (I know, that I have been repeating this for ages, everywhere). The goal is to diagnose the root of the problem, propose solutions, and implement them. In that sense, a design process can be presented as a simple set of questions: 1. What is the problem? 2. Who is affected by the problem? 3. What is the context of the problem? 4. What are the roots of the problem? 5. How can we deal with these roots and solve the problem? 6. What other problems can arise? 7. How can we avoid these new problems or is it worth it to pay that price in the form of new problems to solve the initial problem? I have written a lot about the design process in my book Teoria i praktyka projektowania (komunikacji) (Theory and practice of [communication] design).

How is the implementation of social change supported at the local level (in companies, in municipalities, in local government, in the regions)?

Professor Mariusz Wszołek: Organizations do not differ from municipalities in the last. For a communication designer, these entities are institutionalized systems of communication network, hence the key to their understanding and management is effective communication design. Supporting the implementation of social change is nothing else like animation and moderation – in a systemic sense, it is drawing out organization (from the above example) from an organization, and supporting it by unjudging observation, which will allow the organization (still as an example) maybe independently arrive at conclusions concerning what works, what does not work, what should be changed and how. Then the change is the most effective.

Many research projects carried out by our university are of the implementation kind and they are intended to exert social impact, as part of the so-called Third Mission of Universities. How can social changes designed by our university bring solutions to the most significant social problems, such as the quality of life, social assistance, social justice, gender equality, acceptance of diversity, climate change, etc.?

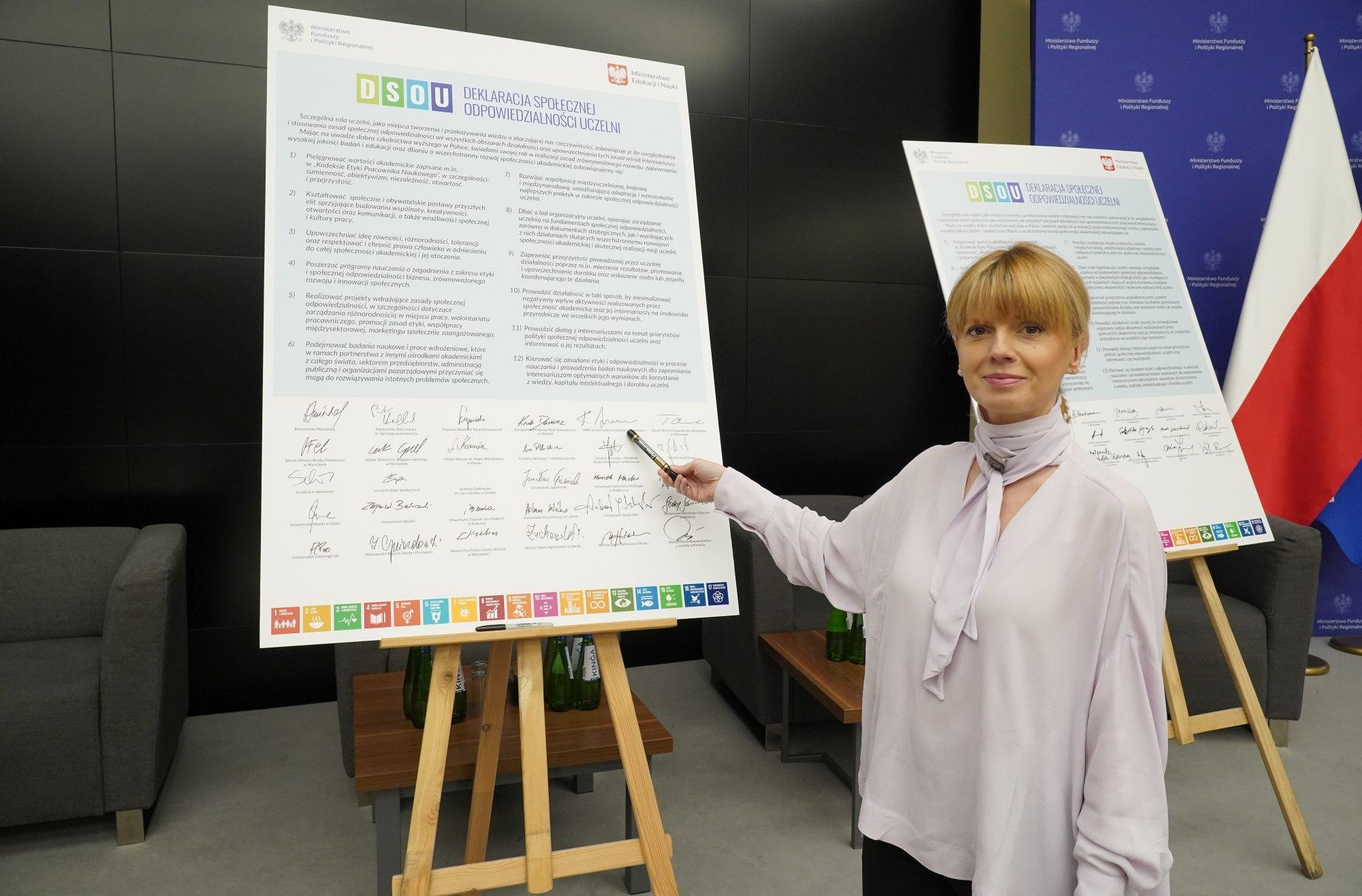

Professor Katarzyna Januszkiewicz: As a university we are the signatory of the Declaration of Social Responsibility of Universities (SOU), which obligates us to take such approach in our research. However, I think that in this community no one treats this as an obligation – we simply work this way. It is clearly visible in truly inspiring projects, which we can boldly say today, have changed the world. Nevertheless, I would like to note a slightly different challenge: how can we measure this impact? And I mean not only indicators, but also deciding when the change has been completed – when a change becomes socially impactful.

These questions are posed not only by researchers, but also by practitioners. While we were working on a project concerning social entrepreneurship, this topic was recurring all the time during our field research. Therefore, our team has developed an Impact Meter, a tool for the description and evaluation of impact any given initiative has on the end beneficiaries. Please note that taking into consideration not only objective but also subjective factors turned out to be necessary, which indicates very well how complex this matter is and how significantly the paradigm of the Quality of Life itself has changed.

Furthermore, SWPS University's Youth Research Center carries out research on life trajectories and life experiences of young people. The researchers focus on adolescents and young adults in various age groups in different situations. They follow life trajectories of men and women in the changing world. They are interested in the experiences of young people in key areas of the process called “transition to adulthood”, including education, the job market, family life, sexuality and parenthood. They also study emotions, internal struggles, and the subjective understanding of “becoming adult” by young people.

This research helps to better understand contemporary young generations and their role in public life. Young generations have always been barometers of social changes and the challenges young adults face are a measure of the state of the economy, the job market, systemic solutions in education, mental health, and parenthood. We use the results of our research to not only implement specific solutions at various levels (e.g., schools, universities, public policy), but also to explain the surrounding world to our students, in a particular moment in history in which they happen to live, study, and enter the job market.

And in what way can our research support pro-democratic attitudes, which are very much needed when trust in politicians is at all times low?

Professor Katarzyna Januszkiewicz: Yes it can, and it can truly be one of the “side effects” of initiatives, which by design do not pertain to civic attitudes. Developing agency will resonate in many areas of one’s activity. Therefore it is worth including this factor at the design phase of an innovation, change, and any action.

Can a change of attitudes towards a phenomenon or a problem also be classified as social change? For example, can we, by now, notice a change of attitudes towards Ukrainians that have settled in Poland after the start of the Russian invasion on Ukraine? Since the beginning, our university has been engaged not only in aid projects, but also in initiatives developing empathy and mutual understanding. For example, our community has published two books that help Ukrainian children to get to know Polish schools and settle in their new classrooms. We also developed a mobile, Polish-Ukrainian, visual dictionary and organized workshops for volunteers.

Professor Mariusz Wszołek: I don’t know. This should be researched. However, if we do not have data from the period before the war or from the very beginning of the war, it would be hard to avoid a certain level of declarative statements. Another question is whether we are talking about transition or about the result. I am not able to assess that, but behind every transition there is some incarnation of social reality, which is not better or worse, but different.

Paulina Woźniak and Joanna Burska-Kopczyk have recently published a book about virtual collaboration – a handbook on creative cooperation in a screen-to-screen mode. This book resulted from the difficulties concerning collaboration during the Coronavirus pandemic. These days the pandemic gradually fades into history, although the experience (e.g., concerning remote work) is worth pursuing further wise development. This book is about these matters, but who knows if it will influence a change of assumptions, attitudes, and the way of working. We will probably be able to assess this some day. On the other hand, if we are talking about something, it means that this something exists in our communication.

How important is close listening to social needs and the right timing when designing solutions required “here and now”? For example, the initiatives undertaken by our university during the pandemic are a good example (a series of podcasts that reduced social fear of the Coronaviurs and the MedStress project) or aid for Ukrainian refugees (two books helping Ukrainian children to settle in Polish schools, a mobile Polish-Ukrainian visual dictionary, and workshops for volunteers).

Professor Katarzyna Januszkiewicz: I believe that this is a crucial element. A project, which is past its “required-by” date, is rather a hobby. Of course, it is difficult, especially in the era of such broad and dynamic changes, but it is indispensable. Therefore, it is so important to search for links between the elements of the system and reflect upon potential consequences of our actions two steps ahead. I think that a good example of this timing is management. Things that are happening in the social context will soon resonate in organizations. Mapping the needs and expectation of various generations on the job market carries very practical implications. It provides us with an opportunity to react in advance and to prepare.

What are the most interesting social change projects that you have been able to implement?

Professor Mariusz Wszołek: I am very proud of two projects that I implemented with students of the Graphic Design program in Wrocław. The first one was the visual identification project for foundations and associations. Using our knowledge and skills, we had an opportunity to help many people who are at the forefront of the struggle for a better world. The second project was called “Polish Wine”, which I supervised together with Radek Stelmaszczyk, Ph.D. and Jan Andrzejewski from Ars Vini company. Our main goal was to co-create visual identity for Polish wine, which is enjoying its umpteenth youth in its history. The idea behind the project was to support local entrepreneurship through usable, useful and actively used design – in this case, packaging design. By working on this type of initiatives, we kill two birds with one academic stone: our students gain valuable experience by working on actual projects, while our local partners receive comprehensive support in the area that is our specialty – visual communication. We invited local vineyards to work with us on the project, and our students of graphic design developed an eye-catching visual identity for their products, i.e., a system of labels and a communication concept. This project proves that a change of the world through design, in this case the world of Polish wine, is possible.

Professor Katarzyna Januszkiewicz: I think that many of our projects carry an element of social change. For example, the project that we have been recently working on with our partners, where the goal is to develop and implement an educational program “Social entrepreneurship - fundamentals”, including teaching materials, and to develop an innovative tool for mapping social innovation trends. This is a truly unique initiative, which I hope, will bring effects in the form of scalable effects. Currently, we are running a course for 30 people, but eventually everyone interested in the area of social innovation will be able to take advantage of this project.

If you had unlimited funds at your disposal, what social problem would you like to research and then design a solution for? Let your imagination run wild!

Professor Katarzyna Januszkiewicz: This is a very difficult question. We are aware of the problems plaguing the contemporary world and we know that sometimes you need very little to change a lot, and sometimes even unlimited funds may prove to be insufficient... Therefore I will turn this questions on its head and will remain on “my playground” of organizational behaviors. The topic I would like to focus on here is the waste of human potential due to the policy of exclusion implemented by organizations. I know that these days everyone writes about inclusivity, but there is a difference between inscribing inclusivity into a company’s mission and vision, and creating a work place for representatives of different groups. I believe, that companies have not assessed the costs of this waste yet. Otherwise, the change would certainly happen much faster.

Professor Mariusz Wszołek: Research is not about money, but about curiosity, and I am aware that it is a bit of a cliché, but this is true. Currently, I am interested in falsehood in communication and how much we need it in our daily operations. Apart from access to a library, I do not have huge financial requirements. Design is another story, although even in this matter I believe in one of the rules of good design formulated by Dieter Rams: good design is as little design as possible.

And because I began with Sadik-Khan, I will also end with her. Ideas devised by her team have always been surprisingly simple: inexpensive municipal furniture, available in local supermarkets or marking the new communication routes by painting the roads with white paint. Design really is not about big budgets, but about good ideas, cleverness in testing and implementation of solutions, and of course the effort of making that design become a reality.

Thank you for your time.

Weronika Książek

Projects referenced in the interview:

Read more about the projects and publications mentioned in the interview::

- The Death and Life of Great American Cities, author: Jane Jacobs.

- Street Fight, author: Janette Sadik-Khan.

- k-EZOP: Elastyczność Zachowań Organizacyjnych Pracowników (k-EZOP: Employees' Flexible Organizational Behaviors), researcher: Katarzyna Januszkiewicz.

- Med-Stres: psychological online interventions for medical professionals, researchers: Ewelina Smoktunowicz, Magdalena Leśnierowska.

- Wina: czyja, a może czyje? (wine labels), the project by students of SWPS University's Graphic Design program in Wrocław, supervisors: Mariusz Wszołek, Radosław Stelmaszczyk.

- Winni są tych opakowań (wine packaging), the project by students of SWPS University's Graphic Design program in Wrocław, supervisors: Mariusz Wszołek, Radosław Stelmaszczyk.

- A series of podcast helping to reduce social anxiety during the Coronavirus pandemic (in Polish).

- Ola, Boris and Their New Friends – a therapeutic story for Ukrainian refugee children, book written by Justyna Ziółkowska and members of the Clinical Psychology Student Research Club in Wrocław.

- Ola and Boris Go to School – tome two of the therapeutic story for Ukrainian refugess children, book written by Justyna Ziółkowska and members of the Clinical Psychology Student Research Club in Wrocław.

- Social entrepreneurship. Fundamentals., Principal Invesigator: Katarzyna Januszkiewicz.